LINES IN TIME: reflections on the art of engraving

Eternity is in love with the productions of time - William Blake

I have always felt and believed that art should ‘speak for itself.’ The language of image is a language in its own right. It has the potential to resonate with certain levels of awareness in the viewer that are beyond words. It is a concentrated, intense language whose numinous meanings may be distorted or diluted by attempts to talk about or translate them into concepts. As such, it is a form of communication best suited to the quiet of contemplation.

But there are many different levels at which any experience of life, including a piece of music or a work of art, may be perceived and understood; and I have discovered a need within myself to provide a bridge between the silence in which the image is born, and the reassuring clatter of concepts–the shared world of ideas, in which the contemplative experience of the image narrows down, becomes more limited but at the same time more accessible to the interpretive mind. This text represents my own bridge between these differing levels of awareness, between active contemplation, or creation, and analytical interpretation.

Lines in time (1997-1998)

Engraving has been the main focus of my work as an artist for over quarter of a century. Occupying the region between sculpture and graphic art, engraving was described by William Blake as 'drawing in copper,' while the 20th century French engraver Roger Vieillard argued that to engrave is “to draw in three-dimensional space.” As an engraving is specifically linear, Vieillard felt that the technique was not suited to representation of the natural, visible world. Rather, the artist is “compelled to express a personal interpretation and a personal vision.” The engraver is like a poet or a writer, “describing his dreams rather than what he sees.”

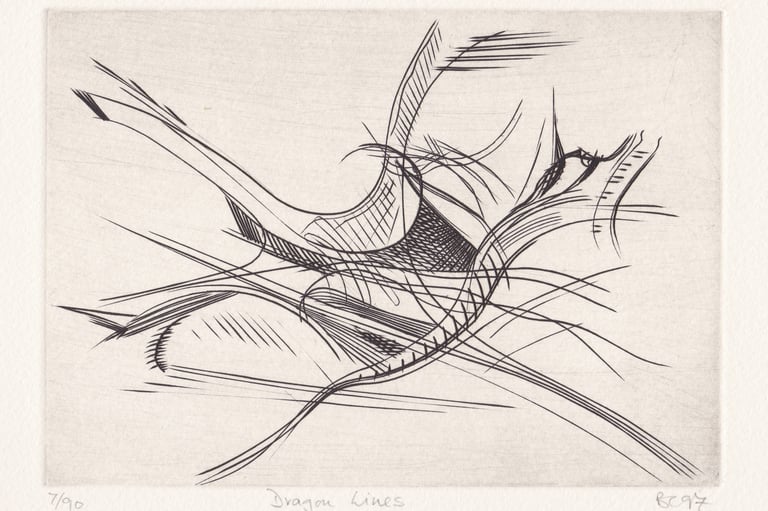

Dragon Lines, (1997) burin engraving on copper, plate size 130 x 185mm

I experience the act of engraving as 'the driven line,' born of a 'secret geometry' - forward action of the steel burin and circular counteraction of the resistant copper plate. Sustaining and mobilizing the opposition between these forces gives rise to the elastic tension and distinctive character of the engraved line. I see my engravings as 'poetry of the driven line,' lyrical images which are sculptural in origin, graphic in destination, and informed by imagination.

My work as an engraver is influenced technically by the engraving of late 15th century masters like Martin Schongauer and Andrea Mantegna, and also by the 20th century renaissance of gravure initiated by S.W. Hayter and Joseph Hecht in Paris. Hayter wrote of Hecht that he “saw the character of life in the line itself, not the description of life by means of the line.” For me this is the essence of engraving. In the act of engraving, marks and lines come alive, communicating an energetic, joyful, elastic tension arising from contact between the cold steel of the burin and the luminous warmth of the copper plate.

For me, engraving with a burin of copper has always been primarily an esoteric activity. Each line driven through the copper possesses its own intrinsic energy, its own integrity and unique purpose. The act of engraving I see as a metaphor for the passage of a life through time–sometimes long, sometimes short. Some lives are deeper, others more faint, some more or less straight, others convoluted.

The point at which the burin penetrates the copper symbolizes incarnation–the point at which spirit enters matter to experience physical life in linear time. It is as if I, as the engraver, occupy a non-physical, transcendent reality until the moment of contact, or impact, between the burin and copper. At that moment a shift in consciousness takes places from the mind of the engraver-observer to the tip of the burin; the tip of the burin represents that aspect of the human spirit which incarnates into the material world to act out a singular life in time.

The moment of contact between burin and copper is like the fall from grace. A certain sense of ‘being driven’ becomes part of human experience. Life now has a beginning and an end; and a degree of spiritual blindness is necessary in order to plough the furrow or path through life. The burin moves, often apparently randomly or mindlessly, through the copper. It is only when it stops–when the line and the life come to an end, or when the state of inner stillness and transcendence is achieved–that it is possible to contemplate one’s life as a whole and see the traces one has made.

The overall engraved image shows how many lines, or lives, are woven together to make up the larger picture–how the individual also belongs to the collective. They are all in a state of ongoing mutual interplay–some lines may seem more important than others but every solitary tiny mark contributes to the whole.